<sound>

↓ ↑ <phonology>

↓ ↑ <morphology>

<syntax>

↓

↑ <syntax>

<semantics>

↓ ↑ <thought>

Linguistics | an introduction

Often times, people

think linguists are translators. This is a misconception. Linguistics is the

scientific study of language. While linguists may study and learn foreign languages

as part of their work, the field is broader than these tasks. Saeed (2003) describes

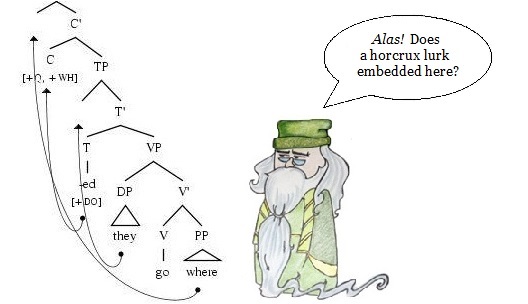

how linguists have traditionally defined languages in modules. The diagram to the

left is a variation of his own hierarchial representation of these modules (p. 9).

Each of its elements are described in detail below. Pursue the following

descriptions to gain a better understanding of how linguists think of

language and general concepts used throughout this project.Phonetics | [fəˈnɛtɪks]

"Phonetics is the study of

the minimal units that make up language. For spoken language these are the sounds of

speech -- the consonants, vowels, melodies, and rythms" (Mihalcek and Wilson, 2011,

p. 36). Different languages contain different sets of possible speech sounds. For

instance, French contains nasalized vowels that English, German, and Slovak do not.

The English "shhh" sound, in words such as Chicago and slush does not

exist in Slovak. On the other hand, the trilled Slovak "r," in zmrzlina ("ice

cream") and štvrtok ("Thursday"), is not present in any of the other three

languages. A further issue is that alphabets often times do not accurately reflect

phonetic information. English is a notorious example of this. Note that the

character "a" in cat versus animal versus

Asia represents very different vowel sounds!Linguists discuss different languages in relation to each other all

the time, and its important that they have means to accurately discern speech sounds

in these discussions. In articulatory phonetics, linguists can discuss

speeech sounds by how they are physiologically produced, or in acoustic

phonetics, linguists can discuss sounds in terms of their physical

properties (Mihalcek and Wilson, 2011, p 36). For the purpose of universally

representing all the sounds of the world's languages, the International Phonetic

Association developed the International Phonetic Alphabet or IPA system. It is an

alphabetic system of notation which attempts to establish individual characters for

every physical speech sound or phoneme (IPA, Handbook).

Phonology | /phonology/

Phonetics is concerned with

the physical properties of speech sounds. Phonology is concerned with how speakers

of a language mentally represent physical speech sounds in their head. For instance,

does cat end with the same speech sound that the word take starts

with? Most native English speakers would respond, "Yes!" However, on closer

examination, we find that this is not the case. The "t" in take is aspirated

while the "t" in cat is not. Native English speakers can test this. Pronounce

each world with your palm facing your mouth at a distance of 1-2 inches. You'll feel

a puff of air as you pronounce the "t" in take but not in pronouncing the "t"

in cat. For native English speakers, the difference between these two

phonemes is not meaningful, and they both are part of the same

allophone, or mental representation (Odden, 2005, p. 2-3, 44).Morphology & Syntax |

[[[morph]V-ologyA]]N &

[NP[[Det][Nsyntax]]]

Morphology is

the study of the internal structure of words (Katamba and Stonam, 2006, p. 3).

Syntax is the study is how words are assembled or ordered to build grammatical

phrase and sentence structures (Carnie, 2013, p. 4). There is extensive interaction

between these two language modules. Consider the English word color. It can be a noun which refers

to physically properties such as "red," "green," "orange," etc. or a verb meaning

"to add color." Morphological markers may be added to color to produce new

words with new meanings, for instance, color-ful and

color-less. From one noun, suddenly we have an array of

adjectives. To the verb color, we can add markings which indicate features

such as person or tense: "He colors," "The girl is

coloring drawings," "They colored." Now consider the

following sentences: "The pages were uncolored," "The

uncolored pages were thrown out," "The

discolored paper can be recycled." Through

morphological marking, a verb (arguably) becomes an adjective, certainly more so in

the last two sentences than the first.

In the above examples, there are a lot of constraints on where or in

what order the different color derivations are able to appear in a sentence.

"He colorful" and "The girl is uncolored drawings" are ungrammatical

sentences. The famous syntactician Noam Chomsky coined the following two

sentences:

(1) Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

(2) Furiously sleep ideas green colorless.

The first is grammatical but nonsensical. The second is both

nonsensical and ungrammatical ("Colorless green ideas do not sleep furiously -- or

do they?" 2008). Syntactic rules govern speakers' perception of grammaticality in

their native language. Of course, the examples so far are restricted to English. It

is important to be aware that meaning and grammaticality is encoded into

morphological and syntactic modules differently across languages. English has little

morphology compared to the Slavic languages where case marking is extensive.

Consider the following sentences:

(1) Robert hit Maria.

(2) Maria hit Robert.

The syntactic ordering is altered between the two sentences, and this

in turn drastically alters their meaning. In the first, Robert is the subject and

Mara is the direct object, i.e., the recipient of Robert's hitting. In the second,

Maria is the subject, and Robert is the recipient of Maria's hitting. Grammatical

rules in Slovak would forbid the same syntactic switch from resulting in the same

meaning switch. Instead, the meaning switch would have to be encoded by case

marking.

(1a) Robert bije Mariu.

(1b) Mariu Robert bije.

(1c) Mariu bije Robert.

(2a) Maria bije Roberta.

(2b) Maria Roberta bije.

(2c) Roberta bije Maria.

In sentence 1a to 1c, Robert undergoes no morphological change and

thus is in the nominative case, meaning he is the sentence subject. Maria is the

recipient of the action "hit." The "-a" to -u feminine singular ending change marks

her as the direct object, and changing the order of the sentence does not over ride

the meaning behind this morphology. Conversely, in sentences 2a to 2c, Robert is the

direct object, as marked by the masculine animate singular suffix "-a." In general,

the accusative case marks the direct object in Slovak in addition to many other

semantic features. There are 4 further cases in Slovak: the genitive, the locative,

the instrumental, and the dative.

Semantics | ∃x(L(x) ∧ S(x))

"Semantics

is the study of meaning communicated through language" (Saeed, 2003, p. 3). A person

can read a sentence and understand all of its phonological, morphological, and

syntactic elements but discerning its meaning often times involve navigating

ambiguity. For instance, consider the English sentence, "I saw the man with

telescope." Is "the man" holding a telescope? Or did the speaker use a telescope to

see him?Logic is used to develop notation intended to clarify ambiguity in

formal semantics. An example of such notation in our header. Where L

indicates "is a linguist" and S indicates "studies Semantics," the notation means

that there are some linguists who study semantics, but not all linguists necessarily

study semantics. This meaning is subtlely but exactly different from other ambiguous

English sentences such as, "Linguists study semantics" or "Every linguist studies

semantics" or "Semantics is studied by linguists."

A distinction can be made between direct and indirect

speech. For instance, "Do the dishes," "Will you please do the dishes?" and "Gee!

The dishes are really piling up" are all sentences with very different surface

forms. The first is an imperative, the second a request, and the last is an

observation. However, depending on context, all three sentences may have the

same semantic core: the addresser is communicating to the addressee that he should

do the dishes.

In comparing two languages, phonetic, phonological, morphological,

and syntactic elements assemble differently in the languages to produce elements

with unique surface forms that nevertheless convey a corresponding if not equivalent

meaning. Compare the following English and Slovak:

(1) Do Žiliny pôjdeme autobusom.

into

Žilina-gen,fem,sing

go-fut

-1per,pl

bus-ins,mas,sing

(2) We will take the bus to Žilina.

(3) We will go by bus to Žilina.

The Slovak verb for "to take" vziať could not have the second

meaing that the English verb "to take" has in sentence 2. Note that "the bus" is the

direct object in sentence two. In sentence three, "the bus" is not a direct object;

it's an instrument and is marked as such by the instrumental case marking "-om."

When "the bus" appears as an instrument in English, no such morphological marking is

possible and instead this feature is marked with the preposition "by."

Cognition| analyzing language with

language

Note that though is somewhat of a hierarchy described as existing

between the modules listed above, they interact top to bottom and bottom to top.

That linguists are attempting to scientifically describe language with language

presents an interesting dynamic! Throughout this project, we will be using concepts

from primarily morphology, syntax, and semantics, in developing hypotheses,

methodology, and in understanding the results of our analysis.  Albus Dumbledore versus Noam

Chomsky

Albus Dumbledore versus Noam

Chomsky